- You’re walking the labyrinth of life. Yes, you’re meant to move forward, but almost never in a straight line. Yes, there’s an element of achievement, of beginning and ending, but those are minor compared to the element of being here now. In the moments you stop trying to conquer the labyrinth of life and simply inhabit it, you’ll realize it was designed to hold you safe as you explore what feels dangerous. You’ll see that you’re exactly where you’re meant to be, meandering along a crooked path that is meant to lead you not onward, but inward.

-Martha Beck

NEWSFLASH in 2015 we will be holding three separate workshops on labyrinths and mandalas with the final one being a community contributions of your own animals and fishes and birds, in a mosaic which will feature an Indian medicine wheel, the Chinese zodiac, the seven paths of initiation, and Buddhist chakras.

In the top paddock at Tingrith before the meetinghouse is a 35metre lavender labyrinth based on the so-called Chartres Maze. The path is 1.5 kilometres to the centre and it takes about an hour to walk around. Technically it is a labyrinth, and not a maze because there is only one way in and out, and there is no choice. The labyrinth, like a mandala, is based on ‘organic sacred geometry’ that departs from the principle ‘the shortest distance between two points is a straight line’, recognising the acceleration found in curvature of vortices.

The Chartres cathedral in which this maze is set, mostly constructed between 1194 and 1250, is the last of at least five which have occupied the site since the town became a bishopric in the 4th century. Even before the Gothic cathedral was built, Chartres was a place of pilgrimage, albeit on a much smaller scale. Today Chartres continues to attract large numbers of pilgrims, many of whom come to walk slowly around the labyrinth, their heads bowed in prayer – an entirely modern devotional practice but one which the Cathedral authorities accommodate by removing the chairs from the nave once a month.

The basic pattern consists of twelve rings that enclose a single path meandering path which slowly leads one to the center rosette, the rose of Mary, though the rosette is not present in pagan versions. The path makes 28 loops, seven on left side toward the center, then seven on the right side toward the center, followed by seven on the left side toward the outside, and finally seven on the right side toward the outside terminating in a short strait path to the rosette

The basic pattern consists of twelve rings that enclose a single path meandering path which slowly leads one to the center rosette, the rose of Mary, though the rosette is not present in pagan versions. The path makes 28 loops, seven on left side toward the center, then seven on the right side toward the center, followed by seven on the left side toward the outside, and finally seven on the right side toward the outside terminating in a short strait path to the rosette

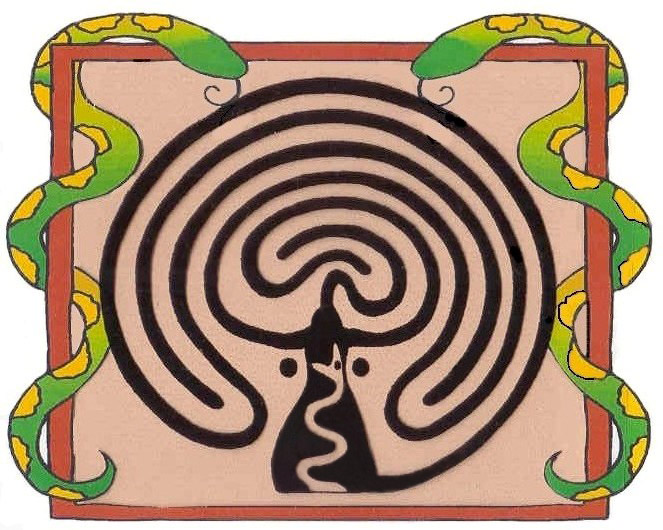

The smaller maze between the meetinghouse and the studio is also called the Dancing Goddess maze or Cretan Maze, not so much because of the maze which Theseus entered to slay the Minotaur, but through the Cretan goddess Ariadne who gave him the thread to find his way out. Ariadne is the Goddess of the shining moon and the dark underworld, and is related to the ancient Astarte, from whom we get the term Easter. So the snakes symbolise death as well as the dance for which Ariadne was known, a celestial spiral motion.

The smaller maze between the meetinghouse and the studio is also called the Dancing Goddess maze or Cretan Maze, not so much because of the maze which Theseus entered to slay the Minotaur, but through the Cretan goddess Ariadne who gave him the thread to find his way out. Ariadne is the Goddess of the shining moon and the dark underworld, and is related to the ancient Astarte, from whom we get the term Easter. So the snakes symbolise death as well as the dance for which Ariadne was known, a celestial spiral motion.

This seven-turn labyrinth is found in many ancient places, one of the more interesting being a three-dimensional maze built into Glastonbury Tor, said to be the largest labyrinth in the world. Upon the surface of the Tor there are seven levels of terracing, some easy to see and some lost in part by erosion. They are the present remains of a great three-dimensional Cretan labyrinth and the same pattern appears on rocks at Tintagel, and among Hopi Indians as a symbol for Mother Earth.

There is a smaller version of the Dancing Goddess maze in the organic garden in Margaret River. You can find out more about labyrinths, including how to make them, from The Labyrinth Society

Life is a journey, and the path is seldom straight. We can bemoan the twists and turns involved in getting from A to B every day (or, to extend the metaphor, from A to Z over a lifetime), but why not celebrate them?

That is one of many lessons taught by the newest attraction on Dr. Weil’s southeastern Arizona homestead. It is a labyrinth, a modern reconstruction of an ancient form that has fascinated people for millennia.

“They are found all over the world,” says Dr. Weil, waving a hand at the 12 concentric circles of stones. “A labyrinth isn’t a maze. A maze is designed to confuse you. A labyrinth has one way in, one way out, and lets you see where you are at all times. It’s really a meditation device.”

The idea of building this one came from Jace Mortensen, Dr. Weil’s friend and gardener, who started the project in February of 2005. Jace decided to copy the pattern of the famed labyrinth laid into the floor of Chartres Cathedral near Paris, France, which was built sometime around the year 1200. Using techniques (see http://www.labyrinth-enterprises.com/tapec1.html) honed by Labyrinth Enterprises, a company that has built these unique structures all over the world, he used a center stake and string to mark the 11 concentric paths and the central chamber, making a pattern 80 feet across, roughly the same size as the one at Chartres. Then he began placing stones on the circles he had drawn with the string and a stick in the hard desert earth.

“A couple of dozen people worked with me on it piece by piece, including Andy and his friends on the weekends,” Jace says, but most of the work was done by Jace, Dr. Weil, and their friend Tamarack Little. They started by placing river rocks that they collected from the nearby wash, but once that became “a little too arduous” says Dr. Weil, “we trucked in enough rock to finish it.”

One of the final acts of construction required Jace to determine the precise position of the sun on the spring equinox. He recalls “standing in the cold morning air, waiting for the sun to rise, and using three sticks to line up the entrance…so the sun’s energy pours into the heart of the labyrinth.” The final rocks were laid in April, 2005, including “lunations,” little spikes around the perimeter that “are supposed to collect and focus energy,” says Dr. Weil.

Even before it was finished, Dr. Weil and others noticed an “odd acoustic pattern” near the center – speaking or clapping hands yields a sort of head-in-a-bucket echo. Probably caused by the focusing effect of sound bouncing off the rock circles, it is nonetheless, “pretty weird,” Dr. Weil says.

Once it was done, Jace came away convinced that, “Anyone can make a stone labyrinth, or just tape one off in their school gymnasium. They can be any size; I built one that’s eight feet across in my backyard.”

As to “doing” the labyrinth, the task is simplicity itself. “You just follow the path,” says Dr. Weil. “It takes about 20 minutes.” He says there is no particular mindset one must bring to the experience, but he notes with a smile that “grimly determined to finish it as quickly as possible,” probably isn’t the best way to go. One of Dr. Weil’s favorite activities is watching groups walk the path. “It’s interesting, because they look like planets, with some of them going retrograde,” he says.

But many people walk it alone. Nancy Olmstead, Dr. Weil’s executive assistant, has done so more than 20 times. “When you are done walking, you experience two things that would seem to be contradictory: you feel really relaxed, and really energized,” she says. “There are not too many things in the world that make you feel that way.”

Jace has also walked it many times. “I like the metaphor,” he says. “One path. One entrance. One exit. We all walk it.” As for the doctor himself, “I would say that it is at least relaxing. It’s a nice walk. It is centering.”

Clearly, I would have to try it myself.

There are actually two adventures here. The first is a heart-in-mouth climb up a steel ladder attached to a swaying eucalyptus tree, which leads to a viewing platform that’s a good 40 feet above the ground. “Being up there gives you another perspective on the labyrinth, on the order and geometry of the thing,” says Jace. As the eucalyptus creaks in the wind, it also gives you some perspective on how many decades it has been since you climbed a tree that high.

The time had come to walk the labyrinth itself. I did so alone on a sunny, cool, early spring afternoon. The first thing I noticed is that what looks like a simple path is, in fact, surprisingly complex. The Chartres design cleverly takes the walker quickly to the edge of the inner circle – which, to the modern mind is clearly “the goal” – and then just as quickly takes him or her back to the outer edge. Close, far, middle distance, far, close, far; then suddenly, I was in the center!

There was a lesson here, but it did not become clear to me until I began the trip back out. The way in had been surprisingly frustrating (would I never get to the center?) but somewhere during the trip out, my attitude changed. Because I knew that simply following the path would take me to the exit, I realized I was free to focus on the walk itself. I was amazed to find a strange, beautiful collection of objects lodged between and atop the rocks: a tiny stone Buddha, several glass beads, a quartz crystal. I had missed most of them on

the way in; but marveled at all of them on the way out.

“I never quite know how they get there,” says Dr. Weil of the artifacts. “People just leave little gifts.” Gifts indeed. The lesson was clear: Focus on the journey. The destination will take care of itself.

By Brad Lemley

DrWeil.com News

Note: On July 31, 2006, the labyrinth was destroyed by a flash flood caused by heavy monsoon rains, but was rebuilt in February, 2007. For those who wish to build their own or learn more, Dr. Weil personally recommends the books, “Walking a Sacred Path: Rediscovering the Labyrinth as a Spiritual Tool,” by Dr. Lauren Artress, and “Labyrinths and Mazes” by Jurgen Hohmuth.

I visited Glastonbury in 1983 and learned of the Cretan Spiral on the Tor. The design of the Labyrinth is very old. The spiral is so far flung it’s not even considered to be of Minoan invention. The same maze can be found as the chief sacred image of the Hopi in Arizona called the “Mother and Son.” The cross at the centre represents the Sun as well as a child being held by the Mother. The Minoan system of writing seems to be big on recording inventories in their palaces, sadly though, very little can be found on their history or mythology that could shed light on what the Labyrinth would have actually meant to the Minoan people.

The design of the spiral is unusual with seven backwards and forward circling before it reaches the centre.

The myriad of Myth and conjecture surrounding the labyrinth is very challenging when you have nothing to relate it too directly, and not knowing its true origin prevents any real prospect of comprehending its actual purpose. With this in mind, I decided to consider an alternative source of information – what if, the Minoan people encoded their beliefs within the Labyrinth itself, using the esoteric nature of numbers. If so, would it is be possible to decipher the meanings of those numbers derived from it? To do this, I would need a system of interpretations, so I borrowed, the archetypes used in the Major Arcana of the Tarot, as a kind of numerology if you will of card numbers, and their meanings from pictures that describe the allegorical nature of the cosmos.

Looking at the Labyrinth, the first Key number is obviously 7 as it is a septenary maze. The second Key number is 28. I calculated this number using the arms of the Cross at the centre and multiplying

4 x 7 = 28

What does the number 28 mean? At first, I thought it might refer to the moon, the number of days it takes to orbit the Earth. Unfortunately, I could not find any Moon goddesses to relate this to, so I had to abandon this avenue of enquiry. If not the Moon, then what else could it be?

It would be a long time before I would understand the meaning of 28. It was not until I came across an amazing book in 2013 that the number 28 finally made sense, “The Lost Empire of Atlantis” by Gavin Menzies. In his book he suggests that Crete was the fabulous city of Atlantis that Plato wrote about, and Stonehenge was built by the Minoans in order to use the stars to navigate by, and travel to America in search of copper to make bronze.

This book helped me with two important conclusions. If the Minoans built Stonehenge, then in all likelihood the spiral on the Tor at Glastonbury about thirty miles away would have been built by the Minoans as well, and if they did indeed go to America, it might explain the Hopi connection to the maze, and their stories of meeting white brothers. With this new avenue of enquiry, I turned my attention to Crete for the first time to see what else it might reveal.

There is a fresco found in 1973 on the Island of Santorini depicting a young woman gathering Saffron. Saffron was used medicinally by women to ease menstrual pains. The Minoan fresco was discovered decorating a room called the “lustral basin”, a cultic room in which it is believed young girls were initiated into the rituals associated with menstruation and childbirth, and found in a building designated as Xeste 3 at Akrotiri. Menstrual pains, the Menstrual Cycle?

I knew Goddess worship was central to Minoan culture, and after careful examination, the number 28 is without a doubt a reference to the average days in a woman’s menstrual cycle.

This is the first part of decoding the Labyrinth. The next part deals with another change to accepted history. I believe the Minoans knew of the seventh planet now known as Uranus. It is possible to see this planet with the naked eye. Due to its slow movement across the sky it would have been mistaken for a distant star. Over time the Minoans at their Stonehenge observatory in England would have come to realise that there is an additional planet to the ones’ already known.

The planet Uranus is unique among the planets. Its axis of rotation is tilted sideways, 98 degrees to the plane of the Solar system. Its north and south poles lie where most other planets have their equators and every forty-two years the poles change position towards the Sun so that one is always in darkness.

The Labyrinth is designed with seven backwards and forward spiraling before it reaches the centre.

Uranus, the Latin for Ouranos meaning ‘SKY or ‘HEAVEN’ was the primordial Greek god of the sky. Ouranos is the Sky Father the son, and husband of Gaia, Mother Earth. He is the Welsh Mabon ap Modron – “Divine Son, son of Divine Mother” when he was banished after Cronus overthrew him, and alluded to in this extract of the spoils of Annwn poem.

‘Well-equipped was the prison of Gwair (Mabon) in Caer Sidi

According to the story of Pwyll and Pryderi.

None before him went to it,

To the heavy blue chain’ it was faithful servant, whom it restrained,

And before the spoils of Annwn sadly he sang.’

Caer Sidi is a place associated with Arianrhod meaning ‘turning’ or ‘spiral castle.’ She is believed to preside over reincarnation, and Caer Sidi is a place of souls to reincarnate after eighty years of blissful forgetfulness.

After watching your video, I know now what I have been doing wrong. Thank you so much for taking the time to make this video for all of us who know something is amiss, but just ca8;2n#17&t figure it out.